Indexes in DBMS

Indexes are very similar to the index section of a book. In books, indexes tell us where a word has been used and provide the page numbers. Just like that, indexes in a Database Management System (DBMS) tell us on what page or block a particular record is present.

So why do we need indexes?

Indexes save us a lot of time. Instead of searching from the start to the end of the book for a specific word, we can simply look up the index and go to the specific pages. Likewise, in DBMS, if we want to retrieve a specific record, instead of searching every record in the database, we can just go to the specific page or block and retrieve the record.

Types of Indices

- Ordered indices: In ordered indices, the index is based on the sorted order of values.

- Hash indices: In hash indices, the values in the index are distributed over a range of buckets, and the value is hashed to get its index entry and then retrieve the location where the value is stored.

Ordered Indices

Clustering index: A clustering index is an index where the order in which the values are sorted in the index is the same as the order in which the values are stored in physical memory. Clustering indices reduce random access and are good for sequential access of records. They are also known as primary indices.

Non-Clustering index: A non-clustering index is an index where the sort order on which the index is based is different from the order in which the values are stored in memory. If we want to access values over a range using non-clustering indices, there will be more random access. They are also known as secondary indices.

Index sequential files: files where the records are stored in a sorted order, and they also have an index based on the value on which they are sorted.

index entry: The search key value together with a pointer to the actual record in memory is known as an index entry.

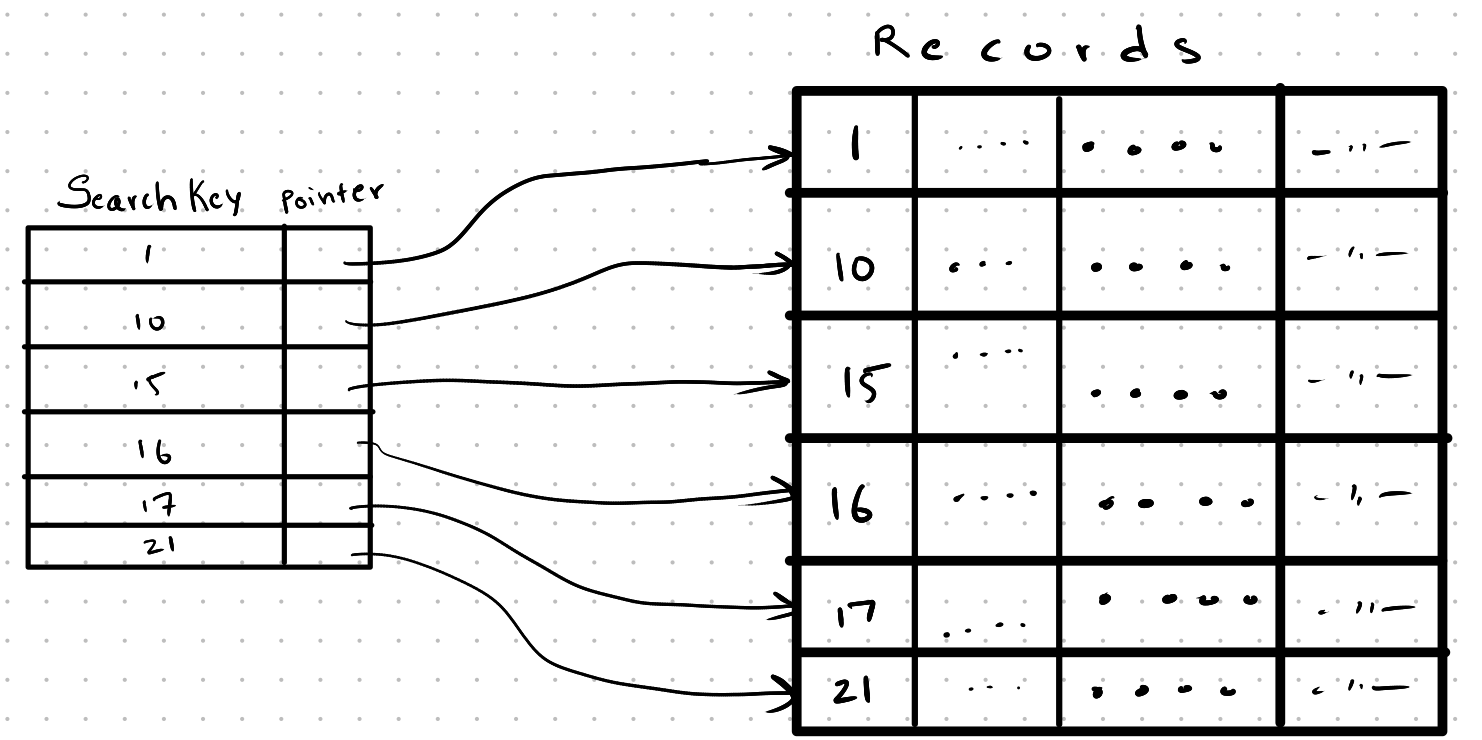

Dense Index

A dense index is an index where there is an index entry for every record present. In case of duplicate search keys, only a pointer to the first record having that search key is stored, and the rest of the records can be found by a simple sequential access as the index is a clustered index.

Dense indices can also be used on non-clustered indices, but the duplicate keys should be handled differently.

Lookups are performed by just traversing the index table, and if it’s based on a clustered index, we can use some optimization such as binary search.

Dense indices

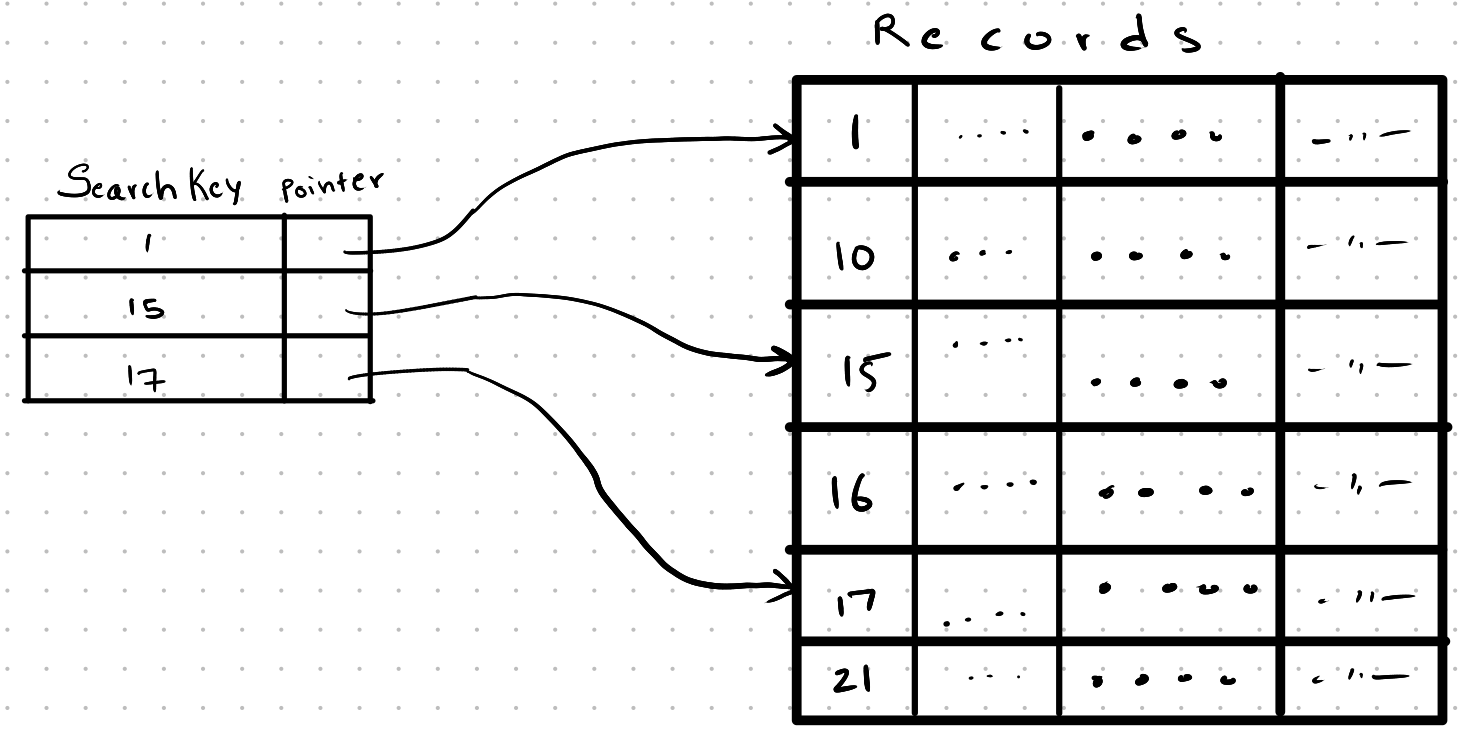

Sparse Index

A sparse index is an index where an index entry is present only for a few records. The size of a sparse index is smaller compared to a dense index. Sparse indices always need a clustering index as the lookup of the records which are not in the sparse index is not possible if it’s not a clustering index.

Lookups are performed by finding an index entry whose search key value is the greatest search key value present in the sparse index which is less than or equal to the search key value we need, and then doing a sequential search from that record.

Example: If the search key value is 55, we aim to find an index entry in the sparse index that’s less than or equal to 55. If the sparse index contains entries like 45, 23, 25, and 35, we select 45. From there, we navigate to the record containing 45 and start a sequential search.

Sparse indices

Multilevel indices

When an index grows too large to fit in memory, searching for an index entry can become time-consuming due to increased disk I/O operations. To solve this issue, we use multilevel indices.

In a multilevel index, the large index table is divided into smaller sub-indices, also known as inner indices. A new index table, often called the outer index or root index, is created, where each index entry points to a specific sub-index of the original large index table. This allows for faster lookup of the relevant sub-index, enabling quicker search for the desired index entry.

Insertion

Dense Index

In a dense index, if a new record is added to the database, it is appropriately placed in physical memory, and then a new index entry is made into the dense index, which points to the record.

If the dense index stores pointers to all the records having the same search key, under one search key, then a new pointer to the record is just added at the end.

Given that the index is a clustering index, If the dense index is storing only a pointer to the first record having the same search key value, then it’s not modified. If there is no index entry having the search key of the record being inserted, we create a new index entry.

Sparse Index

If we assume an search key entry in a sparse index points to a block of records, and the index is a clustering index, then if a record is being inserted, it is checked if the new record holds the smallest value of the search key in that block. If it is, then we replace the old index entry with the new index entry, which points to the physical location of the newly inserted record. If not, it is not modified.

Deletion

Whenever a record is deleted from a relation, it should be removed from all the indices associated with that relation, so that we can avoid inconsistencies in query results.

Dense Index

If a record is being deleted, first the search key value associated with that record is found, and then removed from the index.

If the dense index is storing all the pointers to the records having the same search key value, then the pointer to the record being deleted is removed.

If the dense index is storing only a pointer to the first record having the same search key value, then it is checked if the record being deleted is the first record. If it is, then the index entry is made to point to the next record having the same search key value.

Sparse Index

It is checked if there is an entry of the record in the sparse index. If so, then the index entry is made to point to the next smallest value in that block. If not, the sparse index is not modified.

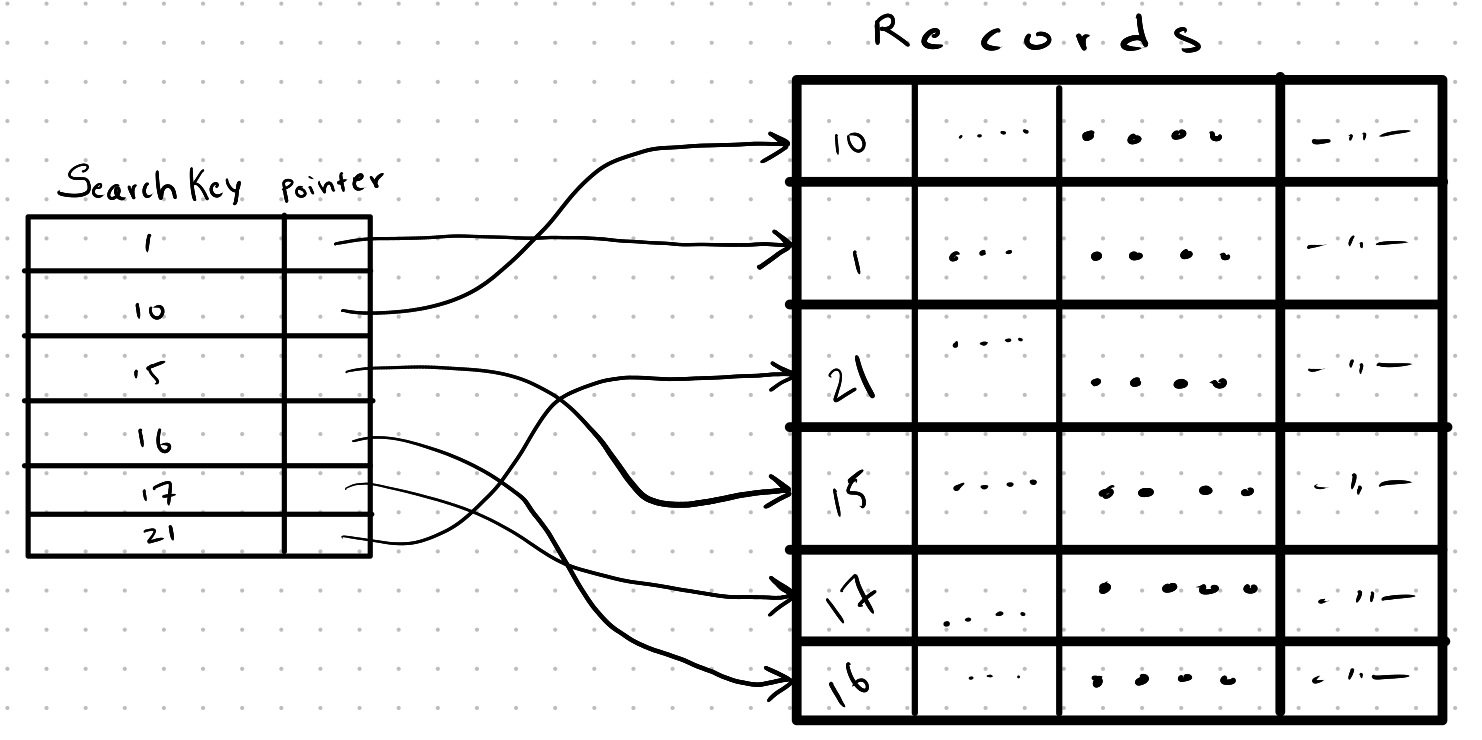

Secondary Indices (Non-Clustered Indices)

Secondary indices are also known as non-clustered indices. Here, the search key on which the index is constructed upon is different from the search key that the records are sorted and stored in memory.

Here, the construction of a sparse index is not possible, but the construction of a dense index is possible. Even though the construction of a dense index is possible, the physical location of the values pointed by search keys might be stored in a different order.

To increase the access time, the search keys are first found, and then sorted based on their physical location, and then accessed.

Non-Clustering index

Non unique search keys

If the search keys are non-unique, that is, whenever they are not based on primary keys, then the DBMS will generally concatenate the primary key to create a composite key of the non-unique search key to make it unique and then store it.

Non-Unique Indices: These are the indices that allow the storage of non-unique search keys.

B+ Trees

The performance of indexes discussed earlier will degrade as the database size increases. However, B+ Tree data structures provide a consistent $O(log(n))$ time complexity for both insertions and deletions. The “B” in B+ Tree is not formally defined but is generally referred to as “balanced.”

B+ Tree is like a evolution of M-way search tree

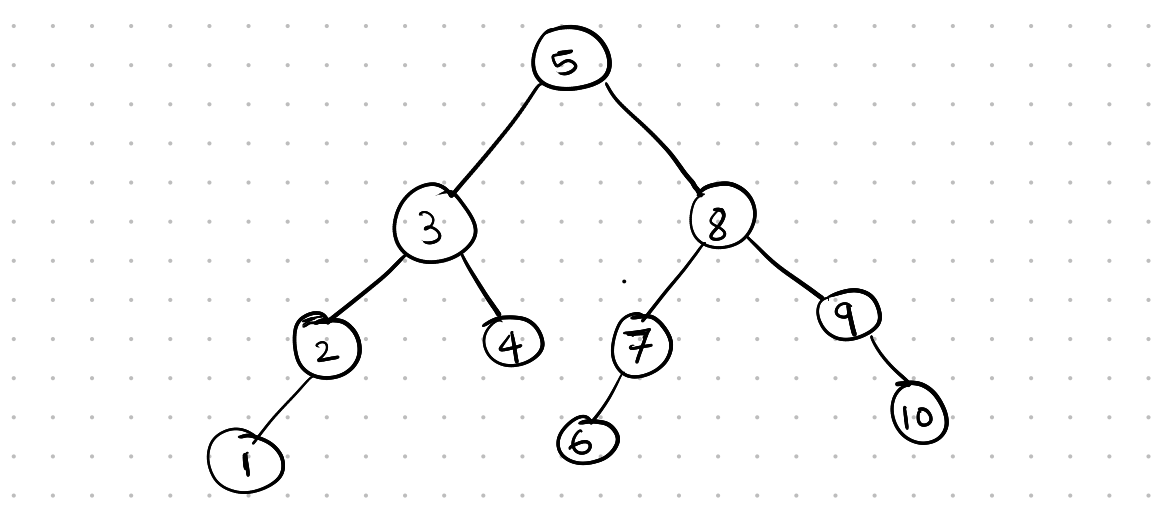

M-way Search Tree

An M-way search tree is an evolution of a binary search tree. In a binary search tree, each parent node has two child nodes: the left child and the right child. The value stored in the left child is less than the value of its parent node, and the value stored in the right child is greater than the value of its parent node.

Binary Search Tree

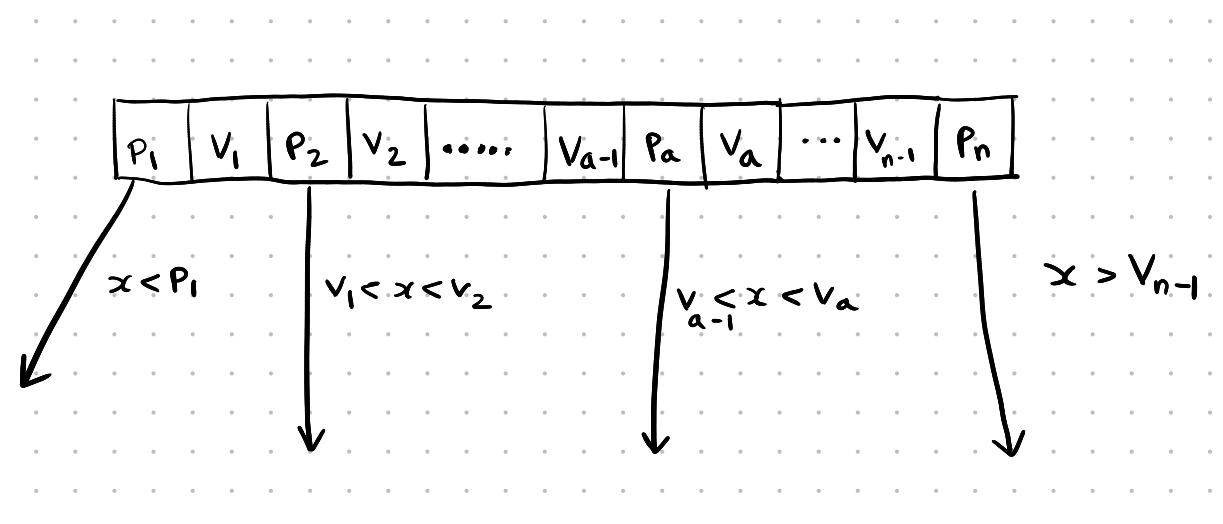

In m-way search trees, the structure of the node is a bit different. Here, each node can store multiple values. An m-way search tree of order n has n pointers to child nodes and has n - 1 values.

Let’s say a node of order n has pointers, p1, p2, ….., pn. and n - 1 values, say v1, v2, v3, … vn-1. The pointer p1 is present at the left end and pointer pn is present at the right end.

The values stored in the child node pointed by pointer p1 will be less than the value v1, and the values stored in the child node pointed by the pointer pn will be greater than the value vn-1. Let’s say pointer pa is present between values va-1 and va. Here, the child node pointed by the pointer pa stores the values that are less than value va and greater than the value va-1.

M way node structure

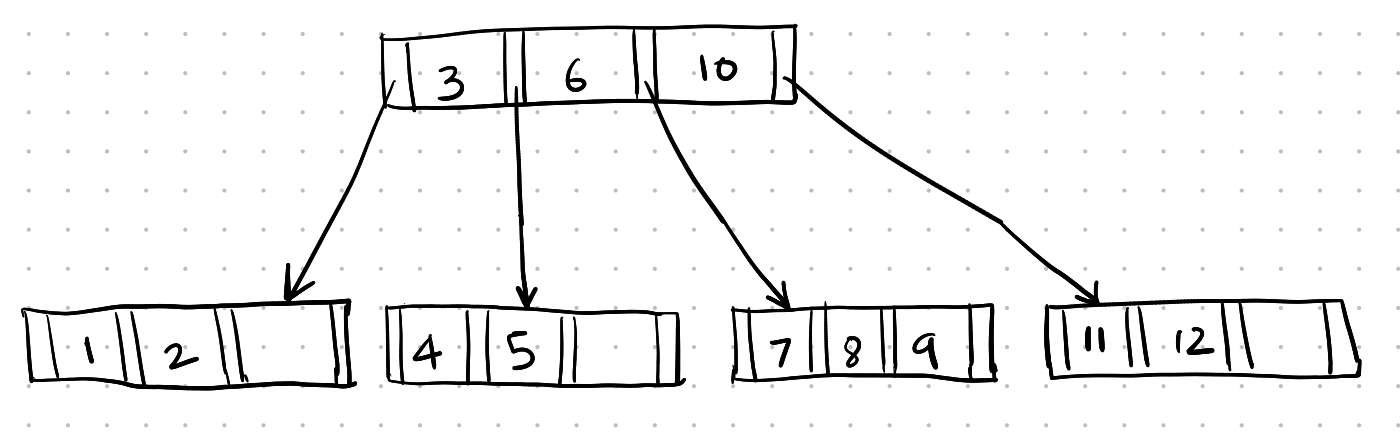

Here is an example of an M-way search tree of order 4:

M-way search tree example

B+ Tree Structure

A B+ Tree is a special type of M-way tree with some additional rules:

- every leaf node is of equal depth from the root node

- every inner node apart from root node is at least half full, that is number of pointers in a node is always greater then or equal to $⌈(n − 1)∕2⌉$

- every inner node with k keys has k+1 non null children

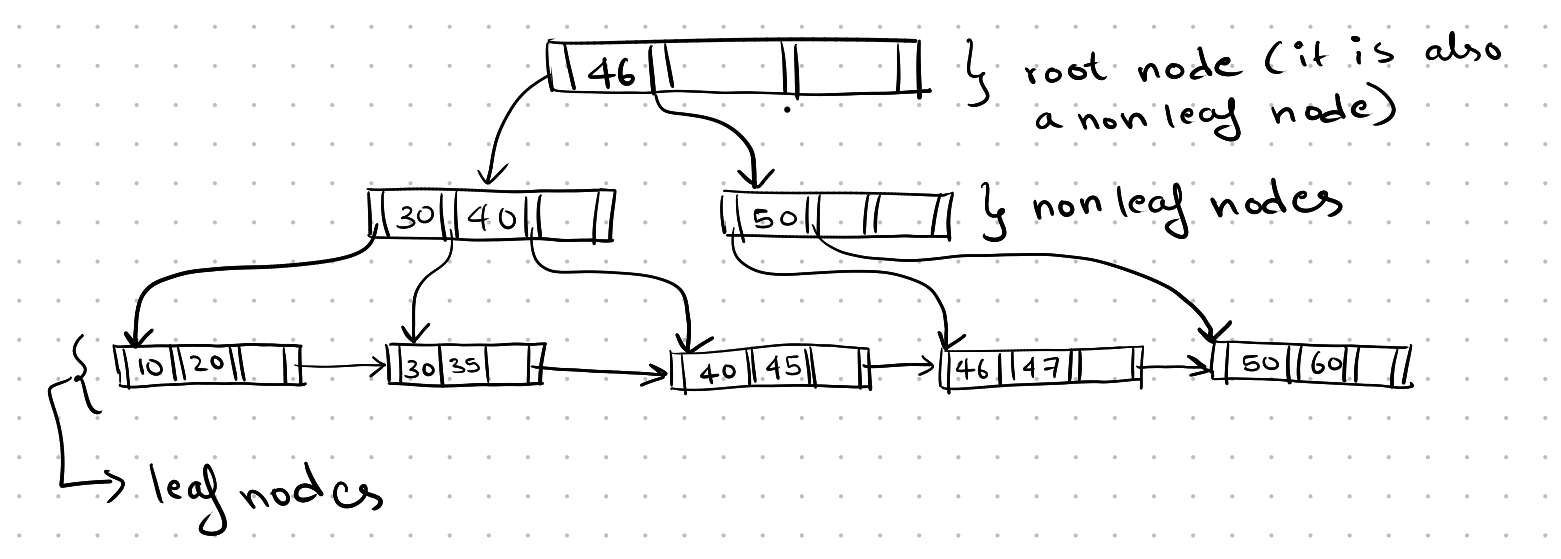

In a B+ Tree, the data that is a pointer to a record or the actual contents of the record are only stored in the leaf nodes. Here is the general structure of a B+ Tree:

B-tree structure

The structure of non-leaf nodes is different from leaf nodes. Pointers in non-leaf nodes store a pointer to another non-leaf node or a leaf node.

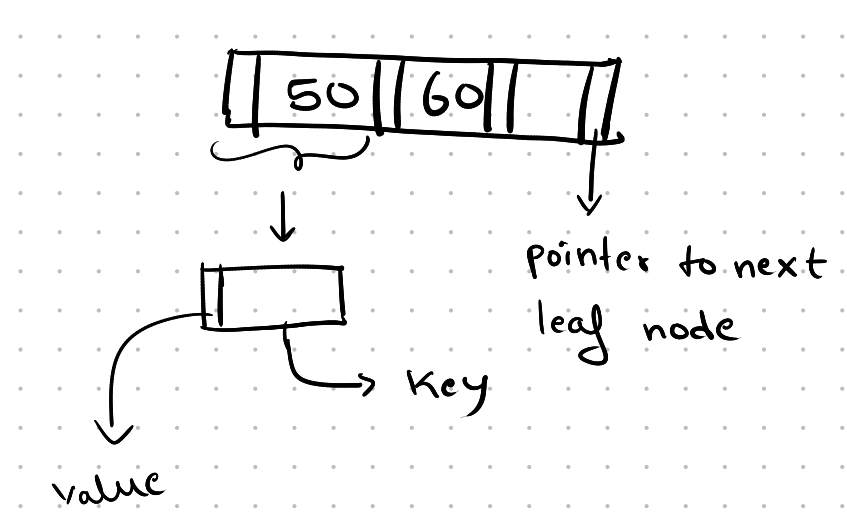

In a leaf node, the value stored may be a pointer to the record containing the search key value or the actual contents of the record.

Here is the general structure of a leaf node. The last pointer of the node points to the next leaf node.

Leaf Node

Insertion

Inserting an index is straightforward if there is enough space in the leaf nodes. If we assume there is enough space in the leaf node, we simply find the node where we should add the new entry and add it.

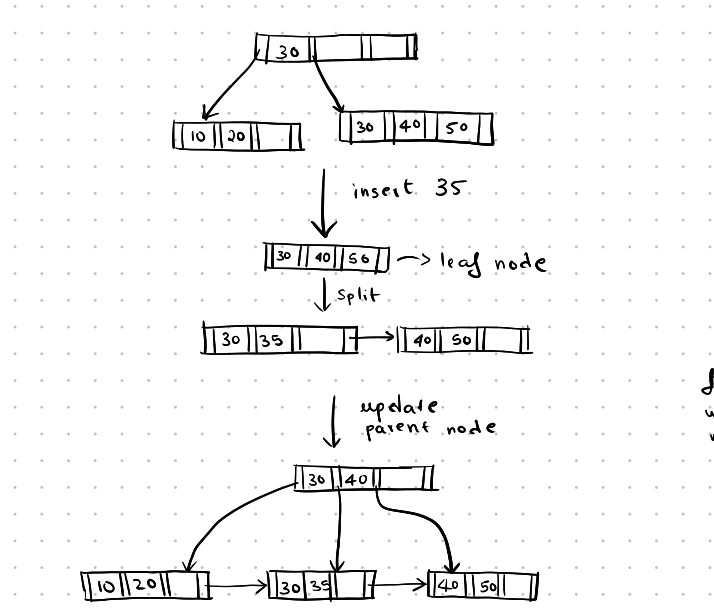

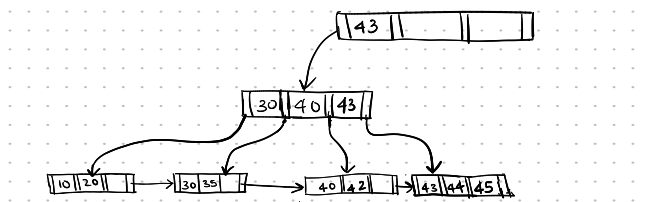

Insertion becomes more complex when there is not enough space in the leaf nodes, and the leaf node must be split. Here is an example of insertion:

If we want to insert an index entry and there is not enough space in the leaf node, the leaf node is split into two nodes. The first ⌈n/2⌉ values stay in the left node, and the rest of the values are moved to the new node. Now, the parent node is updated to include a pointer to the new node.

insertion-1

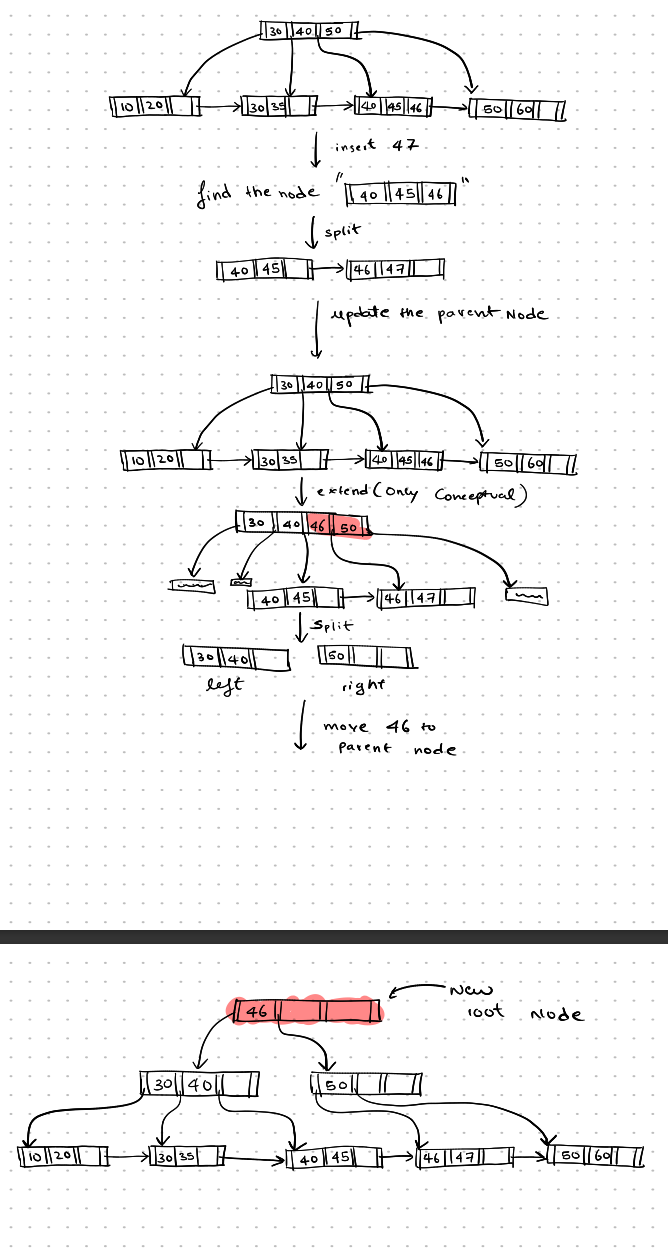

If there is not enough space in the parent node to accommodate the new left node created, we split the parent node. We first assume that there is enough space in the parent node by conceptually extending it. Then, we split the node, and the search key value that is present between the pointers that are kept in the left node and the pointers that are moved to the right node is moved up to its parent node.

In the example below, it’s 46. Here, there is no parent node, so we create a new parent node and add the search key value 46 to it. The new node becomes the root node and also increases the depth of the tree.

insertion-2

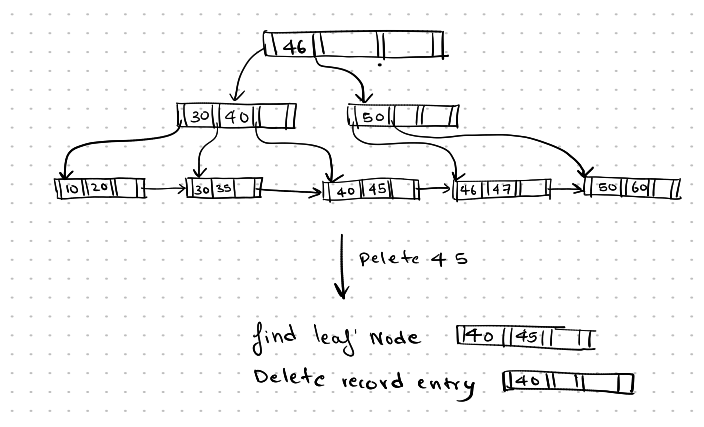

Deletion

Deletion in B+ trees is a more complex process than insertion. If deleting an index entry does not violate the rule of the node being at least half full, no changes are needed, and we can simply remove the index entry from the leaf node.

However, if the leaf node has fewer pointers than the minimum required, i.e., $n’ < ⌈(n − 1)∕2⌉$, where n’ is the number of pointers present in the current node and n is the order of the B+ tree, then the leaf nodes must be merged or pointers in the leaf node must be redistributed.

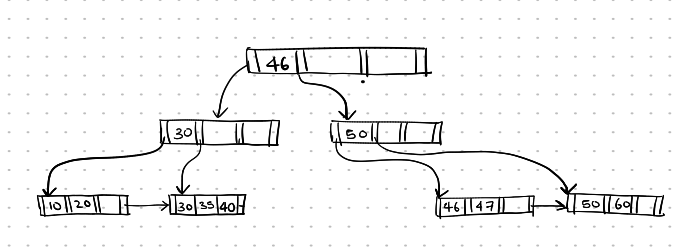

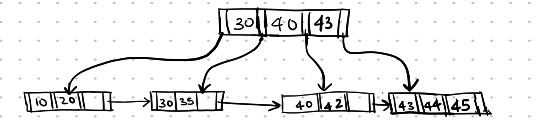

In the example below, we first delete the record 45. Now, the leaf node is left with only one pointer, which points to the search key value containing 40. Since there is enough space in the sibling node, the pointer in the right leaf node can be merged with the left leaf node, and the empty node is deleted, along with the search key in the parent node.

Deletion-1

here is the final state of the B+ tree

Deletion-2

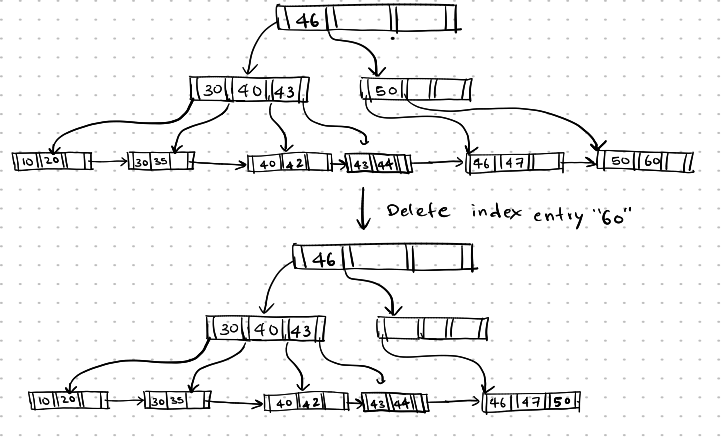

Now, let’s see an example where we need to merge parent nodes. Assume the below B+ tree, and delete the search key 60.

Deletion-3

Here, the search key 60 is first deleted, then the leaf node containing it becomes underfull (it is not half-full). Since the sibling node has enough space to accommodate the remaining pointers, the search key 50 is merged with its sibling, and the search key 60 is removed from its parent node, and the empty node is deleted.

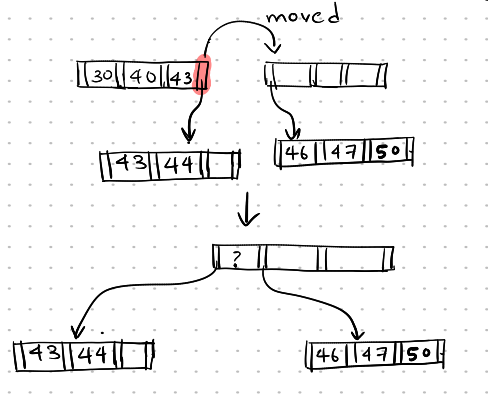

Now, the parent node is underfull, and we cannot merge the pointers with the sibling node as the sibling node of the parent node is full (30, 40, 43). Here, we redistribute the pointers, moving the rightmost pointer of the sibling node to the right node.

Deletion-4

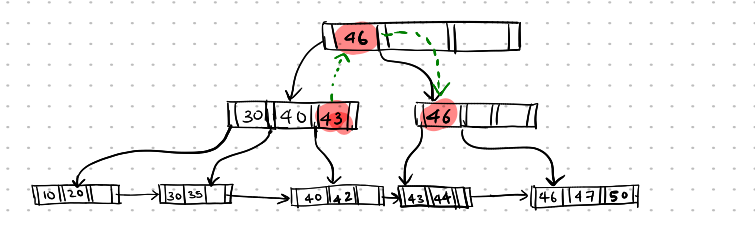

As the pointers are redistributed, the pointer that separates these two pointers is not present in both nodes, but the search key value is present in the parent node, currently separating them, which is 46.

Here, the parent node, i.e., the root node, should also be updated to have the correct search key value. The search key value from the sibling node is moved up.

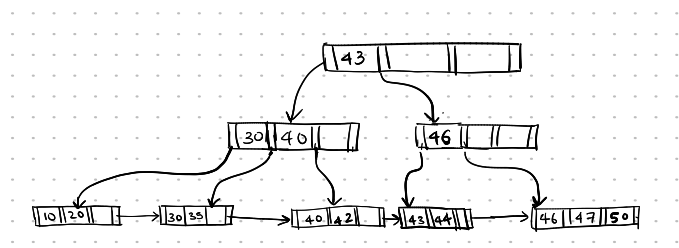

Deletion-5

Here is the final state of the B+ tree structure:

Deletion-6

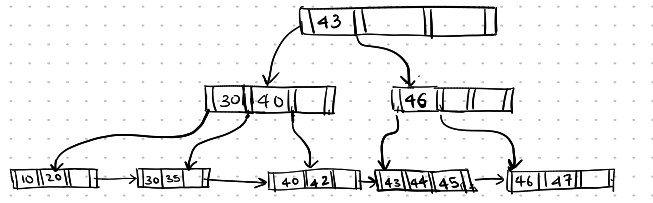

Sometimes, deletion can reduce the size of the B+ tree. Now, assume the below B-tree:

Deletion-7

Now, if we delete the search key entry 47,

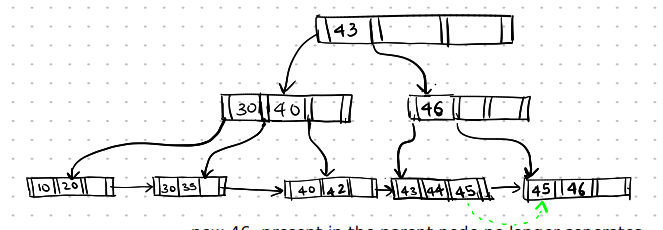

deletion of 47 from the leaf node makes it underfull. Now, the leaf node cannot be merged with the sibling node, so we redistribute the search keys. The rightmost search key 45 is moved left.

Deletion-8

Here, the 46 in the parent node no longer separates the two child nodes, so we correct it by changing it to 45.

Deletion-9

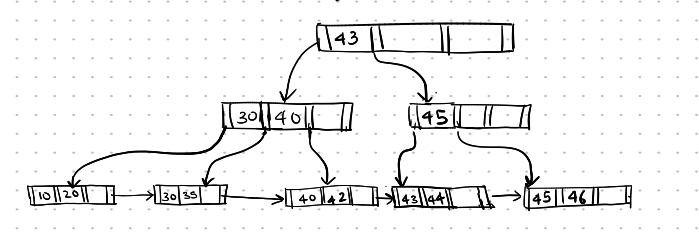

Now, we delete 46.

If we delete 46, the index entry 45 can now be merged with its sibling node, and the empty right node is deleted.

Deletion-10

Now, the parent node is underflowing, and it can now also be merged with its sibling. The search key value separating them is the value present in their parent’s node, which is 43.

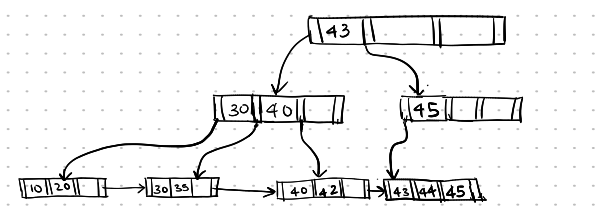

Deletion-11

Now, the root node has only one pointer in it, so the root node is now deleted, and the depth of the entire B+ tree is now reduced.

Here is the final state of the B+ tree:

Deletion-12

Design Choices

Node Size

Generally, large node sizes are preferred over smaller ones, as the larger node size reduces the number of hard-disk access times, which can speed up the process. Typically, the size of each node is the same as the size of a single hard-disk page or block.

Merge Threshold

Sometimes, merging of nodes is not carried out in OLTP databases because the number of insertions and deletions is so high that the overhead caused by merging nodes can be significant. The CPU will spend more time merging nodes than actually performing insertions and deletions. This is also known as thrashing.

Variable Length Keys

Sometimes, the length of the search key can vary, for example, if the search key is a name of different lengths.

Pointer

Here, a pointer to the search key value is stored instead of storing the search key value directly.

Variable Length Nodes

The search keys are stored normally, but the length of the node can change. This method is not generally used due to the large overhead in managing it.

Padding

The size of the search key is fixed, but for the search keys whose length is less, padding is added to make it fit in. This method is also not generally used due to the memory wastage in padding.

Key Map/Indirection

This is the most commonly used method. The structure of the node is similar to the slotted page, where we have metadata storing some information about the node. We then have an array of pointers pointing to the search key values in the node.

Intra-Node Search

The size of the node in B+trees is generally large, so we also need to use optimised search algorithms to find the required search key in the node.

Here are some techniques used to search for the required search key:

Linear Search

Every search key in the node is traversed to check if it is the one that is required. The time complexity is $O(n)$.

Binary Search

The binary search technique is used to find the required search key.

$O(log (n))$

Optimization

Prefix Compression

Most search key values stored in a single node are likely to have a part in common. For example: 10001, 10006, 10009. Here, the search keys have 1000 in common. Therefore, only 1000 can be stored, and then 1, 6, 9 can be stored separately, hence saving some space.

Deduplication

Sometimes, the indexes support the insertion of duplicate values. Generally, a primary key is attached at the end to make it a unique composite key. Here, the duplicate search key can only be stored once, and the records can in turn be differentiated by only the primary key, which saves the space lost in storing the duplicate key multiple times.

Bulk Insert

Sometimes, if we want to create a new B+tree for a relation, then if we insert the search key of each record one by one, it would lead to a lot of splits and would be slow. Instead, we first get all the search keys and their values, sort them, then turn them into leaf nodes and build the B+ tree from the bottom up.

here is the B+tree insertion and deletion example pdf