This blog is a continuation of the database systems series, covering Lectures 5 and 6 of the Database Systems CMU 15-445/645 course.

Buffer Pool

The buffer pool is the memory present in the main memory (RAM) that is used to store pages that are most frequently used, similar to a cache. It is managed by the DBMS (buffer pool manager), because the DBMS can do a better job of managing pages than the OS. If a query wants to read some records that are present on the disk, the corresponding page should first be fetched into main memory and then read.

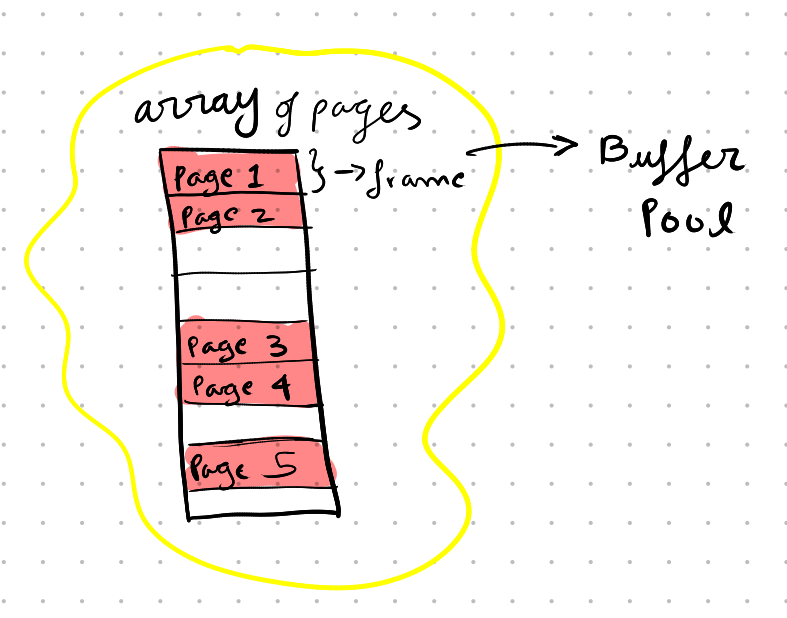

In the buffer pool, pages are stored in an array of pages where each slot is called a frame.

Buffer pools are managed by a Buffer Pool Manager.

Buffer Pool Manager

The Buffer Pool Manager is a sub-system of the DBMS that manages the storage present in the main memory (buffer pool). Accessing pages that are present in main memory is much faster than accessing pages that are present on the disk, as they must first be brought into main memory and then read. Therefore, the main goal of a Buffer Pool Manager is to reduce the number of page transfers from disk to main memory, so that most of the pages required by the query are already present in main memory.

The Buffer Pool Manager needs to store some additional information to manage the buffer pool.

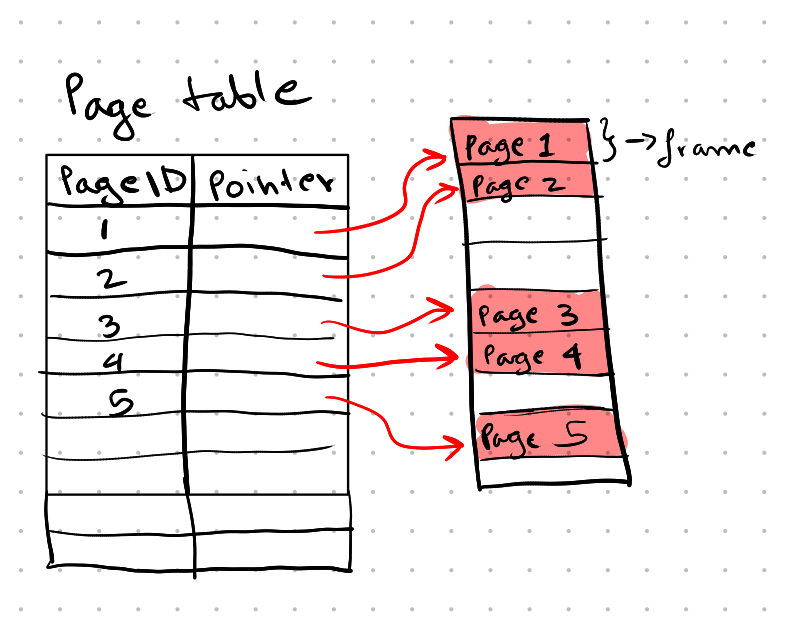

Page Table: The page table is an in-memory hash table used for page lookups. It contains a key-value pair where each page ID is mapped to a frame where that page is stored. If a page is needed, the buffer pool manager checks the page table first to see if the page is present, and if it is, it returns the in-memory address of the page.

If the page is not present in the page table, it is a page fault. The buffer pool manager first brings the page into main memory, updates the page table, and returns the page address.

If the page table is full, one of the pages must be evicted, i.e., one of the pages present in a frame must be replaced with the newly required page.

Note that this page table is also present in the buffer pool and is managed by the buffer pool manager.er

Dirty Flag: For example, if a query modifies a page, in reality, it is actually modifying the page that is present in main memory, not the page that is present on the disk. So, if any changes are made to the page, the page is marked with a dirty flag. All pages that have been marked with the dirty flag are written back to the disk to persist the data.

Output of Pages/Blocks: As we know, pages with dirty flags should be written back to the disk. The output of pages (i.e., writing pages back to the disk) should not be done only when the page needs to be evicted, but should be done frequently or whenever eviction is needed, and writing also depends on other factors. This is to persist the data so that it is safe, and the page can be evicted directly.

Pin/Reference Counter: If a page is being accessed by a thread, the buffer pool manager should make sure that the page is not evicted from the buffer pool. To ensure this, a pin is used. If a thread is accessing a page, the page is pinned, and the buffer pool manager never evicts a pinned page. If the thread completes its operations, it unpins the page, and now the page can be evicted. A single page can be pinned by multiple threads, and a reference counter is used to count the number of threads that are currently accessing the page.

Share and Exclusive Locks: If multiple threads are accessing a page, say one is reading and another is writing to the page, the write operation performed by a thread changes the contents of the page, which will make the contents read by another thread inconsistent. To handle this, share and exclusive locks are used. If a thread is reading the contents of a page, it obtains a shared lock on that page. A page can have multiple shared locks, as the contents of the page will not be changed, and the threads will have read the same data. If a page has an exclusive lock, the thread must wait until the exclusive lock is removed to obtain a shared lock. If a thread is writing to the page, it obtains an exclusive lock. To obtain an exclusive lock, the page should not have any locks on it, i.e., only one process is allowed to have an exclusive lock at a time.

Memory Allocation Policies

There are two types of memory allocation policies: Global Policies and Local Policies.

Global Policies: These policies make decisions in such a way that the entire workload of a database benefits.

Local Policies: These policies make decisions in such a way that only the needs of one transaction are prioritized.

For example, if there are four transactions that the database is currently processing, and three of the transactions require the same page, if global policies are being used, the buffer pool manager will bring in the page that is required by most of the transactions. If the DBMS is using local policies, it might just bring in the page that is required by only one transaction, which might be selected among others by policies such as priority, FCFS (First-Come-First-Served), and others.

Buffer Pool Optimisations

Multiple Buffer Pools: A DBMS can have multiple buffer pools, each managed by its own buffer pool manager. Generally, only one type of page is stored in a buffer pool, but a buffer pool can also store pages of more than one type. For example, one buffer pool manager records pages, and another buffer pool manager stores index pages. This increases performance as each buffer pool can have its own policies for page output, page eviction, etc.

Pre-fetching: Pre-fetching means fetching pages from disk into main memory before a request to access the page has been made. The buffer pool manager can determine which pages are most used, depending on the type of workload, previous queries, and a query will be executed in many steps. The buffer pool manager can predict which pages will be requested in the near future by checking the steps being executed and bring the pages into memory before the request to access the pages is made.

Scan Sharing: When accessing records, a pointer traverses each record in a page, processing one at a time. Since a DBMS typically handles multiple queries concurrently, it’s possible that two or more queries access the same records. In such cases, the pointer traversing the records can be shared among multiple queries.

Buffer Pool Bypass: In buffer pool bypass, some part of the buffer pool memory is specifically assigned to a query process, where the records needed by the query are directly loaded and further used. This is done to avoid the overhead of managing pages in the buffer pool, such as tracking pin/unpin pages, dirty pages, etc. This technique is generally used in large sequential scans. If these pages were normally managed by the buffer pool during a large sequential scan, most of the time would be spent evicting pages, and it would also slow down other concurrent processes.

OS page cache

Generally, the OS keeps its own cache of pages loaded into memory. As the DBMS is managing memory on its own, the pages kept in the cache by the OS become redundant. So, the DBMS uses direct I/O to avoid duplicate page caches.

Buffer Management Policies

If a query needs a page that is not currently in the buffer pool, the buffer pool manager should bring the page into memory and return the address of the frame where the page is stored. But if all frames in the buffer pool are full, then any one of the pages present in memory must be replaced to bring the needed page into memory. It is similar to OS CPU scheduling. The buffer pool manager can use policies such as LRU, FIFO, MRU, CLOCK, etc.

LRU (Least Recently Used): LRU stands for least recently used, as the name suggests. The page that has not been accessed for a long time will be removed from memory and replaced by a new page. To handle LRU, it can be implemented using doubly linked lists (more efficient), where the recently accessed page is moved to the top, and the least recently accessed page is present at the last of the doubly linked list. Alternatively, we can maintain a table (less efficient) containing the timestamps of when the pages are last accessed and update the table whenever new accesses are made. LRU is slow as we need to update the table every time, but it is easy to implement, and it is common that the page that is not being used will most likely not be used in the future.

FIFO (First In First Out): It is a simple policy where the page that is first brought into memory is selected for eviction when all frames are full. It is similar to the workings of a queue. Similar to LRU, FIFO can be implemented using a linked list (more efficient) or by using a table where the time when the page is loaded into memory is tracked (less efficient).

CLOCK: Clock is an efficient but approximate implementation of a LRU policy. Here, each frame is associated with a circular data structure, which is used to store the state flag (reference bit), either 0 or 1, and a pointer, also called the clock hand, is used to traverse these flags. If its flag is 1, then 1 is set to 0. If the flag is 0, the page is selected for eviction. Whenever a new page is loaded into main memory, its reference bit/flag is set to 1. The clock hand performs the traversal around the flags whenever all frames are full and a new page is needed to be loaded into main memory.

A Little Introduction to Indexes: Indexes are used to find the block/page in which the record is stored. For example, if we want to find a record given its ID, we can use the indexes to find the block it is present in and load the block/page into memory and read the record. It is really useful as it saves the work of traversing through every page and checking if the record we want is present there.

Hash Tables

A hash table contains an array of buckets. Where each bucket can store one or more records, usually a small fixed size. It uses a hash function h(x)which takes in a key value and produces a new value ranging from 0 to B - 1, where B is the total number of buckets. The value produced by the hash function is used as an index where the key will be stored.

For example, consider h(x) = x % 10 , and we want to store a simple record, say “id : 10, name : cosmos”, and we are using id as the key. First, the key is passed into the hash function.

h(10) = 10 % 10 = 0 , we get 0, we store the record in the bucket whose index is zero.

The average time complexity of a hash table is O(1) and the worst time complexity of a hash table is O(n).

Hash functions: An ideal hash function must be faster to compute and must uniformly distribute the keys among all the buckets, and there should be no skew in the distribution of buckets. To avoid skewing of the distribution, one must choose a good hash function, and also in hash tables, usually more buckets are allocated than the total number of keys to further avoid collisions.

Two types of hashing: static hashing and dynamic hashing

Static hashing: In static hashing, the size of the hashing table is fixed, and the number of keys are known before hashing. The hash function stays constant and is not changed. A disadvantage of static hashing in DBMS is that the number of buckets in the hash table is fixed, and if the memory allocated to the hash table is very much, then it leads to wastage of memory, and if the memory allocated to the hash table is very little, then it leads to more number of collisions and slower lookups.

Dynamic hashing: In dynamic hashing, the size of the hash table can be changed, it can both grow and shrink. The output range of the hash function is also changed along with the size of the table. A disadvantage of a dynamic hash table is mainly about resizing of the hash table, it is an overhead as the memory should be allocated again, and every record in the hash table must be hashed again. The resizing is generally done when the load on DBMS is less.

Collision handling

A collision is said to occur when two or more keys are mapped to the same bucket index. Here, two methods can be used: open addressing and closed addressing

Closed addressing: Here, a new overflow bucket is used to accommodate the new values in the same bucket index by chaining the buckets (overflow chaining). Closed addressing is generally used in DBMS.

Open addressing: Here, the size of the hash table is generally fixed (but can be resized), and no overflow buckets are used. The collisions are handled by placing the new value in some other index of the same hash table, methods such as linear probing, quadratic probing come under this method.

Static Hashing techniques

Linear Probing

Linear probing uses an open addressing approach to handle collisions in the hash table.

Insertion: In linear probing, if a collision occurs, i.e., there is already a value stored in the bucket (A), then we check if the next bucket (A+1) is empty. If it is, we store the new value there. If not, we again check the next bucket (A+2) and so on. If it is the last bucket in the hash table, we jump to the first bucket in the hash table and continue checking until we find an empty bucket. The initial bucket index is also kept track of so that we don’t loop around the buckets.

Deletion: Deletions are a bit more complex than insertions in linear probing. Say we want to delete a value in the bucket. We hash its key and find its index. Overflow might have occurred, so we must compare the key in the bucket with the key we want. If they are the same, we delete it. If not, we check the next bucket and so on.

If there are three values, and if the middle value is deleted, and if we want to get the 3rd value, we do the linear probe again and see that the next value (2nd) is empty. The algorithm might assume that there is no third value, but it’s not true. To handle this problem, we use different methods

Tombstone Approach: We store a special value in the bucket, which will indicate that an overflowed value is deleted, and there might be some more overflow values in the next buckets.

Movement Approach: In this approach, we move all the overflowed buckets up to occupy the newly deleted bucket.

Linear probing is not generally used in DBMS because the insertion and deletion processes are not efficient, as the number of records might change, and deletions might be performed frequently.

Robin Hood Hashing

Robin Hood is a famous character who steals from the rich and gives to the poor.

Just like the character Robin Hood, Robin Hood hashing also steals from the rich and gives to the poor. So, how can we say that this value is rich and this is poor? This can be done using probe sequence length.

Probe Sequence Length: Probe sequence length is the count of the number of buckets we must probe to get to the key we want. For example, say a hash function hashes a key to the index 0, but due to overflow, those buckets are already filled, and say the key is inserted at the index 2. Here, the probe sequence length (PSL) is 2. Note: If PSL is less, the element is rich; if PSL is more, the element is poor.

Insertion: Insertion in Robin Hood hashing is similar to linear probing. Here, the PSL (probe sequence value) of each key is tracked. If we want to insert a value, we get its key, hash it, and get its index. We check if the bucket at the given index is full. If not, we just insert it there. If it is, we check the next bucket and also check the PSL values (keep in mind that now the PSL value of the key to be inserted is increased by one, as it is now one block away from its hashed index). If the PSL of the key in the bucket is greater than or equal to the PSL of the key to be inserted, we just keep checking further buckets. If the PSL of the key in the bucket is less than the PSL of the key to be inserted (the key in the bucket is considered rich, and the key to be inserted is considered poor), we swap the key present in the bucket with the new key. The old key is again reinserted using the same logic.

Check out this pdf to read more in-depth about Robin Hood hashing.

Cuckoo Hashing

Working on Cuckoo Hashing is similar to the behavior of the Cuckoo bird, which lays its eggs in other birds’ nests and, when those eggs hatch, throws out the eggs of the other birds. Similarly, here, an element occupies the slot of another element and throws out the old element.

It consists of multiple hash tables, each with its own hash function.

Insertions: When inserting an element, the indexes of all the hash tables are calculated using their corresponding hash functions. If any of the buckets is empty, the new element is inserted. If not, one of the buckets is randomly selected, the new element replaces the old element, and the kicked-out element is reinserted into the hash table using the same logic. To prevent infinite loops, it allows only a limited number of reinsertions.

Dynamic Hashing Techniques

Chained Hashing

Chained hashing is the simplest form of hashing technique, in which a linked list is used.

Insertions: When inserting a value, if the bucket to which the key is hashed is already full and the pointer stored is null, a new overflow bucket is allocated, and a pointer to this new bucket is stored in the old bucket that was full. Now, the new value is stored in the newly created bucket. And if there is a pointer to another bucket, and if a slot is empty in it, the value is inserted there. If even that bucket is full, and there is a pointer stored for another bucket, the other bucket is checked, and so on.

Linear Hashing

Linear hashing performs incremental growth of the hash table, where the hash table is not directly doubled in size, but a new bucket is added when an overflow occurs. It uses two hash functions and a pointer known as the split pointer to keep track of which bucket to split next.

Insertions: Here, just like every other algorithm, we hash the key and find its hash bucket. If it is empty, we insert it there. If it is not, a new overflow bucket is added. Keep in mind that the overflow bucket can be present in linear hashing, but the number of overflow buckets is generally reduced as the algorithm proceeds. After the new overflow bucket has been added, another new bucket is added to the hash table, and a new hash function is used, say h2. Now, the values in the bucket to which the split pointer is pointing are rehashed again using the new h2 hash function, and the split pointer is made to point to the bucket.

Lookups: Lookups are a bit more complex here. Say we want to look up a value; we first hash it using the original hash function h1. If the indexed bucket is present before the split pointer, we rehash it again using the h2 hash function to get the bucket in which it is stored. And if the hashed bucket is present after the split pointer, we use the original hash function itself, so no rehashing is required.

The linear hashing performs splitting in a round-robin fashion and performs the splitting in the form of rounds. When a round is completed, the split pointer is reset to the 0th bucket. A round is set to be completed if all the initial buckets (those buckets that are present before the expansion) are split.

Extensible Hashing

Extensible hashing is a dynamic hashing method in which the table is grown and shrunk as requests are made. Usually, the size of the hash table is doubled when growing and halved when being shrunk. Note that even if the size of the hash table is doubled, buckets are not assigned yet, and new buckets are only created when a key is hashed to it. They are only allocated when they are needed. The method uses the first n bits of a hashed value to find the index of the key. Here, the number of first n bits used is called the count. A global count is stored for the entire hash table, and every bucket has its own local count.

Insertions: Here, the first n bits of the value generated from hashing the key are used as the index. If there is an empty slot in the bucket, it is inserted there. If not, we first check if we want to increase the size of the hash table. This is done by checking the local count of the bucket and the global count. If both are the same or the local count is greater than the global count, then there is only one element in the hash table that points to the bucket. So, we increase the size of the hash table. We increment the global count by one (n + 1, so now the first n+1 bits are considered), effectively doubling the size of the hash table. For every two entries in the hash table, we make them point to their original bucket, and for the bucket where the overflow occurred, we create a new bucket and assign the second entry to point to the newly created bucket. Then, we retry the insertion, which will now be mostly successful.

If growing the hash table is not required, we just create a new bucket and assign the second entry pointing to the same bucket to point to the newly created bucket. Then, we retry the insertion, which will now be mostly successful. However, if all the values present in the bucket have the same search key, splitting will not solve the problem, so we must have some kind of way to handle large amounts of duplicate search keys.